This picture taken on 19 March, 2016 shows Buddhist monks and members of the Muslim community joining a meeting for interreligious exchange and understanding in order to reduce conflict in Thailand’s restive southern province of Narathiwat. (Madaree Tohlala / AFP Photo)

When speaking of religious intolerance in ASEAN member states, it’s likely that images of marginalised Rohingya in Myanmar, the increasingly conservative stance of Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo seems to have recently taken, and clampdowns on the Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transsexual (LGBT) community in Muslim majority countries like Malaysia and Brunei are among the first pictures that come to mind. More recently, however, a report has surfaced of a mosque in Bangkok – in existence for more than 100 years – which has lately become the subject of many anonymous complaints about the loud daily prayers conducted there.

Sombat Wongsamai, a 68-year-old adviser to the Imam (prayer leader) of Bang Uthit Mosque in Bang Khao Laem district, said the mosque, in response to the complaints, has lowered the volume of its loudspeakers, but the complaints are still coming.

The Bang Kho Laem District Office apparently received complaints about the mosque too and has sent officials there several times to check the volume levels of the loudspeakers used for daily prayer gatherings. “But every time measurements are made, the mosque is found to have complied with noise standards and the volume has never exceeded 80 decibels,” Sombat said.

The complaints could be seen as a worrying sign as religious intolerance has been steadily increasing not only in the region but globally as well. It is even more worrying considering that Thailand has never had any serious problems with religious intolerance before.

Last year, the International Panel of Parliamentarians for Freedom of Religious Belief (IPPFoRB) launched a four-part report that looked into the religious challenges in Southeast Asia, namely the rise of religious-based intolerance, discrimination against minorities or native peoples, securitisation of freedom or belief in fighting terrorism, and the need to uphold international human rights standards in this context. The report noted that religious freedom appeared to be regressing in Southeast Asia and that serious challenges had arisen in recent years across the region, such as in Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia. However, in Thailand’s case, the report said there was no serious concerns for freedom of religion or belief.

Deep South insurgency

The IPPFoRB’s report also mentioned that despite Thailand’s government stating that the conflict in the South of the country was not a religious one but caused by social and economic inequalities, the IPPFoRB said that the treatment of Muslims in South Thailand was still a concern.

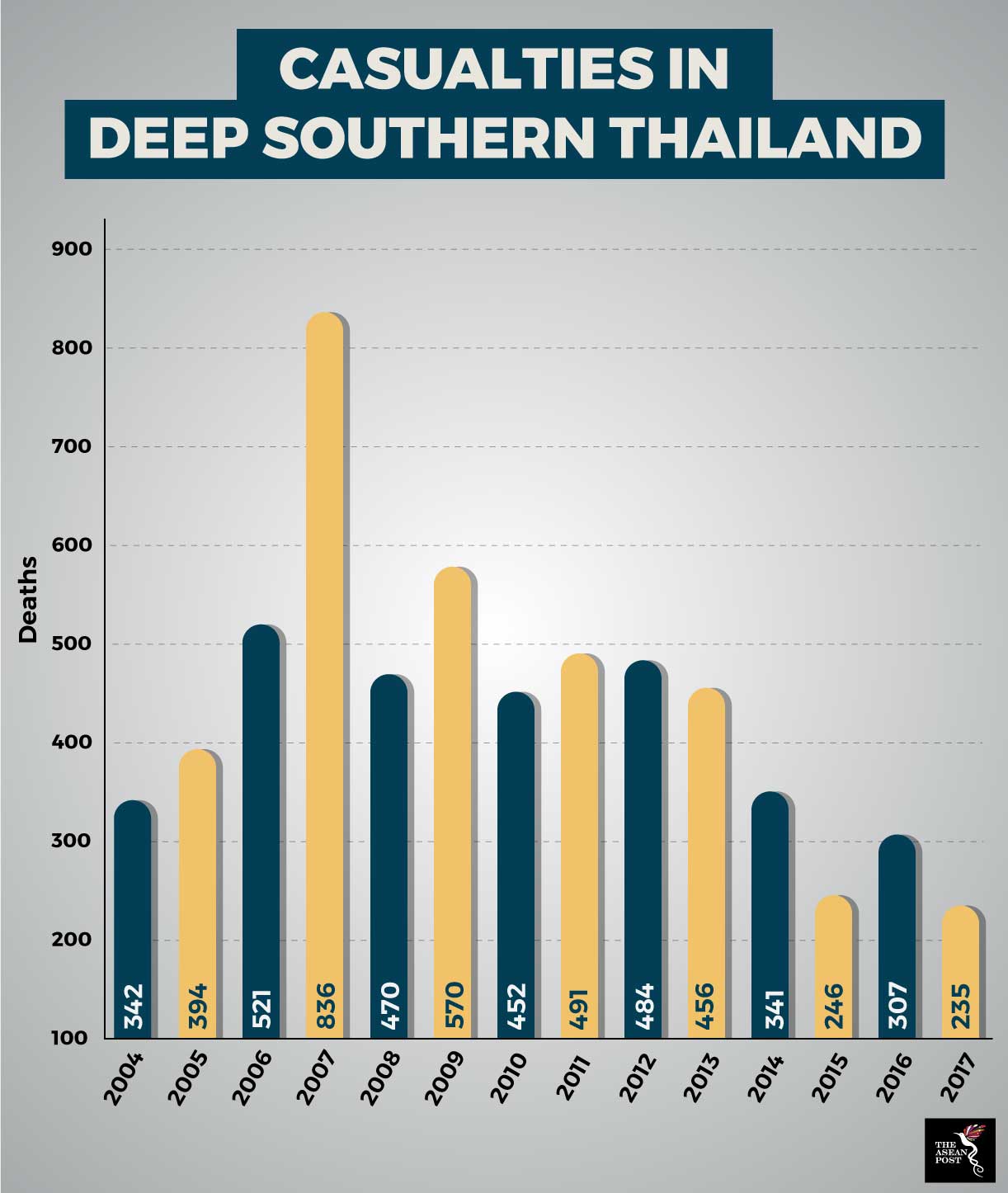

It is interesting to note that despite a drop in insurgency related violence to an all-time low, the violence – previously contained within the deep South – seems to have spread to other parts of Thailand as well.

In August 2016, two blasts struck Patong beach on the island of Phuket while three more explosions were reported further South – two in the southern town of Surat Thani, killing one, and another blast in Trang, which also left a person dead. Two more explosions also occurred in southern Phang Nga province. A military source told the media on condition of anonymity that he considered the August bombings to be an expansion of the insurgency, partly as a test for new recruits.

Source: Deep South Watch

Last year, regional media reported that the deep South conflict had indeed hurt relations between Buddhists and Muslims in Thailand. Quoting Buddhist monks, the report noted that Buddhists and Muslims in the South had lived together peacefully in the past but things have now changed.

Head monk of Muang district in Yala, Phra Rachamonkol Wuttajarn, told the media that in the past, people of different faiths helped each other even on religious-related matters but now they have taken a different attitude.

“Some see Buddhists as victims and interpret events linking the violence to Islam. Or they think that Muslims gave their support to those behind the violence. People have lost trust,” he said.

Conditions for jihad

While most experts agree with the Thai government that religion has very little to do with the deep South insurgency, an increasing intolerance has the potential to change this scenario.

A report released last November by the International Crisis Group, Jihadism in Southern Thailand: A Phantom Menace, noted that to date, there is no evidence of jihadists making inroads among the separatist fronts fighting for what they see as the liberation of their homeland, Patani.

Nonetheless, it also warns that southern-most part of Thailand appears to offer conditions favourable for jihadist expansion. “A Sunni minority that constitutes a majority in the conflict zone; a Muslim insurgency with a narrative of dispossession at the hands of non-Muslim colonisers; and a protracted conflict with frequent repression and violence by Thai authorities,” the report said.

“Thai officials, analysts, and even some in the militant movement have expressed concerns about prospects for jihadist influence,” the report added.

The concern here is that if tensions continue to rise between minority Muslims and majority Buddhists in Thailand, then a conflict which is currently nationalistic in nature could end up turning religious, giving rise – as the International Crisis Group puts it – to jihadism.

The International Crisis Group advocates direct talks between leaders of the insurgency and the government as a priority to avoid such a scenario from becoming a reality.