Residents queue before receiving humanitarian aid in Palu, Central Sulawesi on 7 October, 2018, following the 28 September earthquake and tsunami. (Mohd Rasfan / AFP Photo)

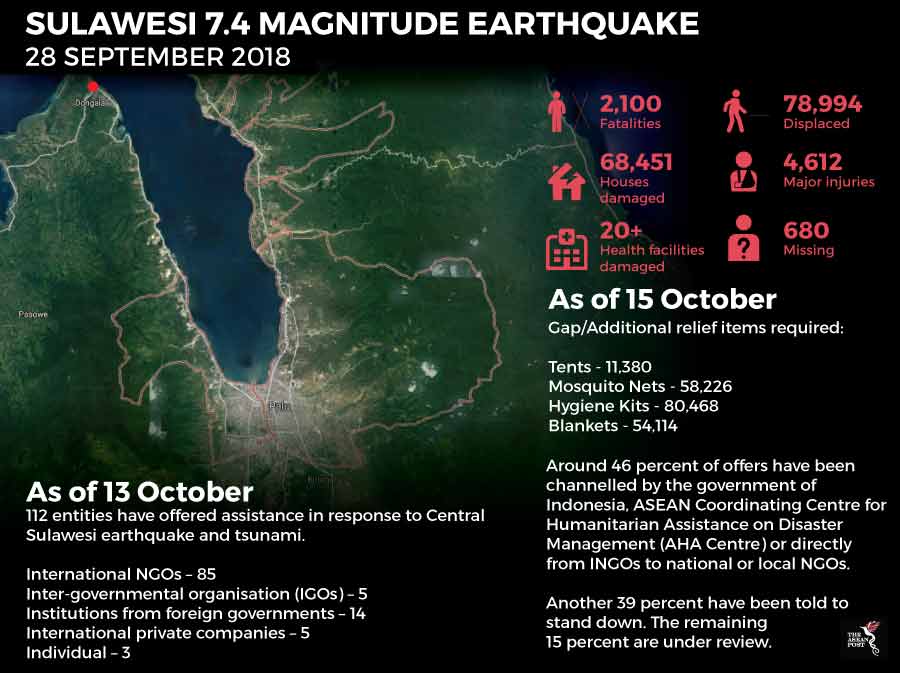

The tsunami-triggering 7.4 magnitude earthquake which took place on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi on 28 September, has resulted in major destruction, liquefaction and landslides in the cities of Palu and Donggala, as well as in the surrounding areas. As of 15 October, the earthquake that was followed by almost 700 aftershocks, has claimed 2,100 lives with more than 4,600 injured, while another 680 people are still missing. More than 68,000 homes have been damaged, displacing 79,000 people.

The authorisation of urgent foreign aid for humanitarian efforts in Sulawesi by President Joko Widodo, aided by the gruesome images from ground zero, triggered a tsunami of offers for international assistance from around the world. Some humanitarian operatives have also flooded the transportation hubs in the region, heading for Sulawesi.

However, reports have surfaced of independent foreign aid workers and foreign humanitarian organisation being ordered to pull out of the disaster areas, while others have faced difficulties securing entry permits for staff and equipment.

Rerouting assistance through local machinery

The Indonesian National Disaster Mitigation Agency (BNPB) has since released rules for foreign non-governmental organisations (NGOs) wanting to join in the rescue and relief efforts. This includes enforced registration with the BNPB, restriction of foreign citizens and NGOs from working directly in the field, as well as aid assistance and relief item distribution by government agencies and local partners only.

The departure from the usual way of delivering humanitarian assistance for disasters has triggered confusion among the many humanitarian organisations who are concerned that aid delivery to victims might be hampered. Another concern is that their foreign counterparts would not be able to support the overworked, and traumatised Indonesian staff and volunteers.

On the part of the government, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has denied that they are preventing foreign aid workers from entering disaster areas, saying that they are only required to do so in consultation with national agencies. Its spokesperson, Arrmanatha Nasir, in a statement, said that all assistance from foreign governments is coordinated through the Foreign Ministry, while relief efforts by international NGOs are coordinated by the Indonesian Red Cross.

“We do not want to end up in a situation where we are receiving assistance and already have adequate supplies or capacity on the ground, while we are not receiving the assistance we truly need, or capacity we lack on the ground. We can end up in a situation where there would be so many foreign aid workers or volunteers with good intentions that it can actually hamper rescue and recovery efforts,” Arrmanatha explained.

Source: ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on Disaster Management.

A relook at humanitarian aid delivery

For some, the operational restriction enforced by the Indonesian government is understandable. Head of the Humanitarian Policy Group at the United Kingdom’s (UK) think tank, Overseas Development Institute (ODI), Christina Bennett, said that international donors and NGOs may have gotten used to the usual way of carrying out humanitarian work, jumping in when a major disaster takes place. However, their efforts in marshalling resources and supplies through a team of global staff can at times overtake or overwhelm governments and local aid responders.

“I think there has been a lot of recognition in the past couple of years that maybe this isn’t the best way. I think gone are the days when you’re going to have a humanitarian sector that comes into a disaster situation with a very heavy footprint and sets up as almost an auxiliary, or a replacement of government services,” she said.

Humanitarian and Human Rights Advisor at the Australian Council for International Development (Acfid), Jennifer Clancy, said that international NGOs had to walk a careful line of not acting paternalistically in delivering aid. There is a need to recognise that the Indonesian government, the Indonesian Red Cross and other Indonesian NGOs have significant capacity for providing humanitarian assistance.

“Natural disasters aren’t a new phenomenon for Indonesia, unfortunately. They are well experienced in responding to natural disasters. There’s pushback against the international community who come flooding in days or weeks later, taking over the response. It’s about taking back that power and saying local organisations have significant capacity,” said Clancy.

It needs to be pointed out that both, the Indonesian government and international NGOs are looking out to avoid factors that may hamper their aid delivery. The disruption in how humanitarian work is carried out is sometimes key to improving systems. However, disrupting the traditional way of doing things must be managed carefully to ensure that it is not at the expense of those affected by disasters.