On 22 May 2014, the military clique in the name of “National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO)” seized power from the Yingluck Shinawatra government citing as its pretext the incessant violence which has led to massive casualties among people and damage to properties, hence the seizure of the power to stem the destructive causes.

Submitted by admin on 20 May 2015 15:30

On 22 May 2014, the military clique in the name of “National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO)” seized power from the Yingluck Shinawatra government citing as its pretext the incessant violence which has led to massive casualties among people and damage to properties, hence the seizure of the power to stem the destructive causes.

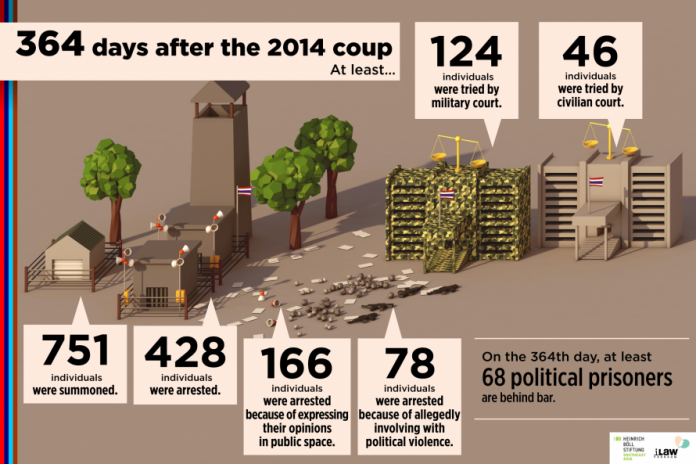

After the coup, at least 751 individuals were summoned by the NCPO. At least 424 were deprived of liberty. Some have been forced to undergo “attitude adjustment” to reeducate them about the necessity for the military to seize the power and then let go. Meanwhile, at least 163 individuals have been pressed with political charges. The NCPO has imposed Martial Law and then issued the NCPO Order no.3/2015 to ban political gatherings, restricting freedom of the press, and forcing civilians to be tried by Military Court. At least, 71 public activities were intervened or cancelled by the use of military force.

Please note that some refference links may avilable only in Thai

The summoning of individuals

During the one year after the coup, from 22 May 2014 to 22 May 2015, at least 751 individuals have been summoned by NCPO. The summonses were made through different ways including broadcasting the names on radio and TV and other informal means. Some have received a phone call asking them to have some food or coffee (with military officials). Some saw military officials visited them their residence simply to invite them for a meeting [Read more about the evolution of summoning and visitation under Martial Law].

Comparatively, those who are affiliated with the Phue Thai Party or the Red Shirts have been summoned proportionately more than other groups, or at least 278 of them while, at least 41 individuals who were affiliated with the Democrat Party or the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) and the Network of Students and People for Thailand Reform (NSPTR) were summoned. In addition, at least 176 academics, activists, students, writers and journalists have also been summoned by the NCPO. Most of them have to sign a release form which basically prevents them from participating in any political activity and/or requires that they have to ask for permission from NCPO prior to making any travel abroad.

At least 22 of them were pressed with charges after they reported themselves to the NCPO. Six were prosecuted with lèse majesté charge or violation of the Penal Code’s Article 112. Apparently, apart from being a venue to bring in individuals for “attitude adjustment” program or to prevent individuals from participating in political activity, the summoning has been used as a shortcut to bring in people against whom the authorities want to press charges. [See the list of individuals charged with cases related to politics after the 2014 coup]

Among them, there are at least two suspects who died in custody including Pol. Col. Akkharawuth Limrat and Mr. Surakrit Chaimongkhol.

An emerging trend of lèse majesté cases after the coup

The lèse majesté prosecution against prominent persons alleged to have claimed their connection with the royalties

As far as it could be documented, prior to the coup, only two individuals faced lèse majesté charge as a result of their bragging about connection with the royal family and committing fraud including the Assawin and Prachuab cases. But after the coup, at least 30 individuals were pressed with cases regarding the violation of Article 112 simply because they were accused of claiming their royal connection for personal gain.

It started with the arrest of Mr. Chairin, Secretary General of the “Glory of the King Office” in November 2014 followed by the arrest of high ranking police officials including Pol Lt Gen Pongpat Chayapan and Pol Maj Gen Kowit Wongrungroj in the same month. Several other prominent figures were purged the same charge including close relatives of the former Princess Consort Srirassami.

[See a special report on the use of Article 112 against persons accused of claiming their royal connection to commit fraud and the list of individuals facing the charge against Article 112 as far as we can collect.]

The rising number of lèse majesté convicts and the arrest and raids against internet radio

During the one year after the coup, at least 46 individuals have been charged for violation of Article 112 to stifle their freedom of expression. This is comparatively high considering that prior to the coup, there were only five remaining convicts on lèse majesté charge and five cases pending in the Court.

The massive raid or the eradication of “Banpot Network” accused of producing and distributing audio clips containing political criticisms has led to the arrest and charging of at least 16 individuals. It started with Chaleaw who was summoned to report himself to the NCPO and faced legal action for his alleged uploading of Banpot audio clips into file sharing sites. He was sentenced to three years with suspension by the Criminal Court. Then, “Kawee” was arrested, but was then released for unknown reasons.

Early 2015, Hassadin, who was accused of being the voice of “Banpot” and others, altogether 14 of them, were nabbed on 24 April 2015. 12 of them were indicted by the Judge Advocate in the same case, while Tara and “Chaba” were indicted in two separate cases. They are awaiting hearing schedule to be fixed by the Military Court. There are well over 400 Banpot audio clips distributed online since 2010, but the arrest just happened now.

At least five individuals were charged for violating Article 112 after they had reported themselves as summoned to the authorities including Thanat, Khatawut, “Jakkrawut”, Siraphop and Pol.Sgt.Maj.Prasit. The arrest of a number of lèse majesté suspects was carried out by military officials, and they were held in custody and interviewed invoking Martial Law including Pongsak, Chayo, Anon, Tiansutham, Opas, Patiwat, etc.

The Military Court doubled lèse majesté sentence

The Penal Code’s Article 112 provides for imprisonment of 3-15 years. Previously, the Court of Justice often sentenced a guilty person to five years per count.

But after the coup, an announcement has been made effectively to authorize the Military Court to try certain cases against civilians including lèse majesté cases. In the one year after the coup, the Military Court delivered at least four verdicts on lèse majesté cases relating to freedom of expression including the cases against Kathawuth, “Somsak Pakdeedej”, Thiansutham, and Opas. In the cases against Kathawuth and Thiansutham, the Military Court sentenced them each to ten years per count whereas in the case against “Somsak Pakdeedej”, the Court sentenced him to nine years per count, and the case against Opas, three years per count.

Apparently, the Military Court has doubled the penalty rate in lèse majesté case. In the case against Thiansutham who was accused of making five facebook postings, he was sentenced to altogether fifty years, prior to be reduced to 25 years given his pleading guilty. It was the most severe punishment in Article 112 case that iLaw has ever documented.

The arrest and prosecution against mentally ill persons

At least three suspects in Article 112 cases were arrested after the coup and have been sent for mental examination while continued to be held in custody. The three of them are “Tanet”, Samak and Prachakchai. As for the cases against “Tanet” and Prachakchai, it was reported that prior to the coup, the police had approached them and after talking to them, they had decided to drop charges against the two persons finding they were mentally unfit. Still, after the coup, they were arrested and pressed with charges.

As for .Tanet., according to mental examination, he was found to suffer paranoid. Even, the cash of 300,000 baht was placed as deposit, the Court denied him bail.

Restriction of freedom of assembly and public activity after the coup

After the coup, the NCPO issued the Announcement no. 7/2014 banning political gathering and imposing punishment including imprisonment for not more than one year or a fine of not exceeding 20,000 baht or both. During May to June 2014, a series of anti-coup activities were organized, and at least 63 individuals were arrested, of which 24 were pressed with charges concerning the violation of the political gathering ban. All were convicted and sentenced to suspended terms. None of them has been put in jail so far. After June, the anti-coup activism has been in recess, until the “Citizen Resistant” organized an activity in February 2015, as a result of which the four organizers and participants were arrested and pressed with charges concerning the violation of the political gathering ban.

16 March 2015, 4 persons who were the accused in the “My Dear Election case” sang together with students who came to show their support in front of the Bangkok Military Court. The four were released after the court rejected a pre-trial detention petition filed by the police

Event cancellation, asking to speak at the event: Intervention of public activity by the military

Public events which are outright not anti-coup activities including public discussion, theatrical performance or movie screening, though have not been banned completely, but have to face intervention or censorship.

From our documentation, in the past one year after the coup, at least 71 public gatherings and events have faced invention or censorship by the military including 22 public gatherings and 49 other events including public discussion. In terms of issues being censored, events concerning history and politics were censored or intervened the most (33 times) followed by issues concerning land and community rights (12 times).

The intervention or censorship is dependent on issues to be raised at the events. For example, if the events are concerned with politics or military, they were often totally banned such as the public discussion on “the demise of dictatorships aboard” organized by the League of Liberal Thammasat for Democracy (LLTD), which had to be called off in the middle, or the public discussion on “Justice Under Construction” organized by the Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR), which had to be postponed.

Other activities which have faced intervention included the public discussion on “Rights and Freedom of People under the Draft Cyber Security Act” organized by the Santi Prachatham Library which was attended by military officials in uniform and was recorded with still picture and audio throughout the event. One of the military officials even asked to speak as a resource person. The public discussion on “Na Moon EIA: Injustices of Land Petroleum Exploration in the Northeast” at the Mahasasakham University was allowed to proceed given that the organizers had to refrain from criticizing the performance of the NCPO junta regime, showing any resistance sign and military and police officials have to be invited to participate in the event.

Sanitation Act: The freedom which can be exercised at the expense of fine

Under the military regime, laws to crack down misdemeanors including the 1992 Sanitation Act have been invoked to impede the exercise of freedom of expression. The laws do not intend to impose hefty penalty, but has incurred unnecessary burden for those who want to exercise their right to freedom.

From our observation, there are at least four cases in which the persons who have simply exercised their right to freedom of expression were fine invoking the Sanitation Act including the case of relatives of those who were killed during the 2010 demonstration who distributed leaflets in a public place and were fined 5,000 baht as the maximum rate, the case of students hanging black banner to commemorate the 19 September coup on a flyover in front of the office of Thai Rath newspaper or the case of students hanging a banner criticizing the 19 September coup on a flyover on Pyathai Road, both of whom were fined 1,000 baht each, or the case of Polwat who distributed leaflets in Rayong opposing the coup, who was fined 500 baht.

The use of Computer Crime Act to criminalize villagers opposing the military

From our documentation, there are at least three cases in which the authorities have filed charges against villagers who posted pictures or videos during the contentious dispute between them and the villagers.

On 4 January 2015, Maitree, an ethnic Lahu, was pressed with charges concerning the violation of the Computer Crime Act after he uploaded a video clip showing the situation when negotiation between the villagers and the military was taking place. In the video, it was narrated that the military official was accused of slapping one villager in his face. The event stemmed from the incidence that a man clad in military like uniform has gone into Ban Kong Pak Ping in Chiang Mai and slapped in the face of a villager while he was sitting near a fire. The villagers demanded the perpetrator be brought to justice. A meeting was called, and the video of the incidence was uploaded, which has led to a report against the villager.

On 23 March 2015, an Assistant Subdistrict Headman in Tambon Doonsad, Kranuan District, Khon Kaen, has reported a case to the police against two villagers as the admin of Ban Na Moon-Doonsad Conservation Group facebook page which has been campaigning against the petroleum exploration project by the Apico (Korat) Co Ltd on libel and violation of the CCA. The case stems from the posting of the pictures of the Assistant Subdistrict Headman in the facebook page, and a number of comments in the post could be considered slanderous to him.

After the coup in January 2015, more military personnel have been deployed in Ban Na Moon-Doonsad to provide security to the petroleum operation including the transportation of equipment into the area.

On 24 March 2015, the Internal Security Operations Command Region (ISOC) in Chaiyaphum Province summoned Adisak, an employee of fire control unit. He was inquired about the pictures of military officials who raided the farmland of villagers in Ban Kham Noi, Chaiyaphum, which were posted in the Assembly of the Poor’s facebook page. In the post, it was accused that the military forced the villagers to sign in a paper to concede the land to the authorities. Adisak admitted to taking the phone, but not posting them. Later, he was summoned by the Chaiyaphum City Police Station as he was pressed with a charge concerning the violation of CCA.

After the declaration of the Tad Tone National Park overlapping farmland and residential area of the villagers in Ban Khom Noi, the head of the Tad Tone National Park and the villagers have met and agreed on marking the land the villagers are allowed to use temporarily. But after the NCPO Orders no. 64/2014 and 66/2014 were issued to suppress deforestation, the military and forestry officials have been implementing strictly the forest conservation policy leading to the incessant eviction of villagers from their traditional land.

Source : freedom.ilaw.or.th