A mother carries her daughter during a rally organised by Muslim politicians against the signing of the UN anti-discrimination convention (ICERD) at Merdeka Square in Kuala Lumpur on 8 December, 2018. (Mohd Rasfan / AFP Photo)

On 8 December 2018, downtown Kuala Lumpur was engulfed in a sea of white by those celebrating the government’s decision not to ratify the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination or ICERD.

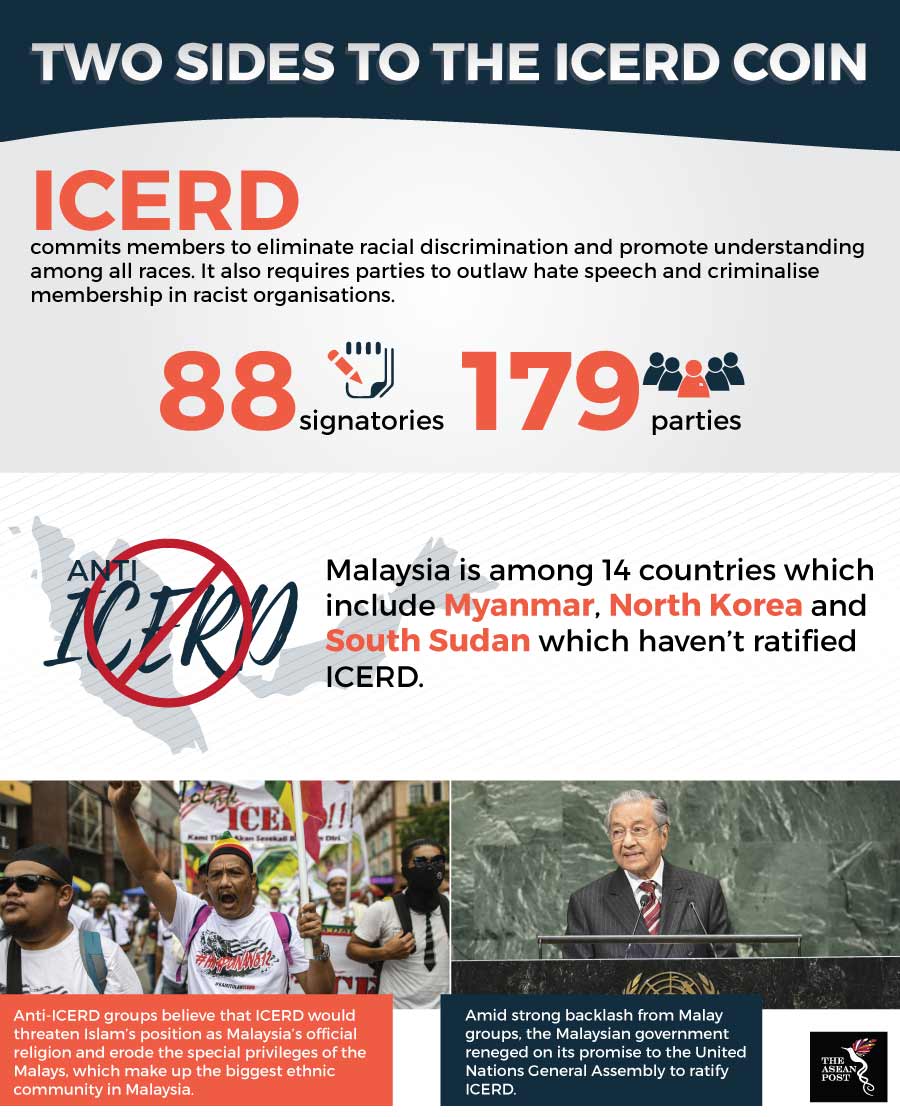

What initially began as a protest against the Malaysian government’s decision to ratify the convention turned into a celebratory spectacle after the government rescinded on its promise a few days prior to the slated rally.

Malaysia’s ratification of ICERD would have signalled to the international community its willingness to comply to international human rights standards. Under the stewardship of a new government, the country has posited a vision to be more proactive in international affairs.

Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad pledged at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in September, that the country will ratify all remaining core United Nations (UN) instruments related to the protection of human rights, including ICERD.

Malaysia’s Foreign Minister, Saifuddin Abdullah said in October during the country’s Universal Periodic Review that the new government will pay particular emphasis to human rights advocacy on the international stage.

At a time when Islam has received erroneous criticisms through no fault of its own, Malaysia’s international standing as a moderate Muslim nation is crucial in combatting the global trend of rising Islamophobia. To allay unfounded and incoherent fears of the religion, Malaysia has rightly adopted a principled approach, embracing the universality of values such as human rights.

But the U-turn on ICERD is a spanner in the works and indents Malaysia’s reputation on the international stage – a telling break from the norms of Malaysia’s foreign policy which has its roots in Malay historiography.

Historical reading of foreign policy

Prominent Southeast Asian historian, Dr Anthony Milner, details in his monograph on a historical reading of Malaysian foreign policy that the emphasis on “reputation” and “prestige” alongside the fostering of kindred relations even to polities that are vastly different from their own has long been a cardinal factor in pre-Malaysian diplomacy.

Using historical records, he demonstrates how the past sultanates of Kedah and Malacca placed great importance on receiving recognition from historical powers like the Chinese and Ottoman Empires which helped bolster an image of prestige for the sultanate. Nevertheless, the sultanates remained resolute in their cultural and religious matters despite desiring recognition from these greater empires.

This trait carried on to post-independence Malaya and then Malaysia. Former Deputy Minister Dr Ismail Abdul Rahman was keen for Malaysia to be “respected” internationally. Dr Mahathir in his previous term as prime minister was concerned with Malaysia having a “good image.” Even embattled former premier, Najib Razak insisted that Malaysia embrace a “principle-based foreign policy.”

Viewed in this spirit, Malaysia’s ratification of ICERD is seemingly a no-brainer. However, the opposition’s agenda proved to get the better of the new government.

ICERD was branded “un-Islamic” although most Islamic nations including Saudi Arabia and Indonesia have already ratified it with some reservations – a ratification model that Malaysia could emulate. It was decried as a threat to the “special position” of Malays as enshrined in the Malaysian constitution.

Source: Various

However, legal experts in the country believe that ICERD is actually in line with the Malaysian Constitution.

Constitutional expert, Dr Azmi Sharom pointed out that there exist provisions in ICERD, which “allows for affirmative action as long as it is necessary.”

“This is the same position as the constitution,” he reiterated.

“The “special position” is fundamentally permission for the Malaysian government to breach the equality provisions of the Constitution via affirmative action. But it is only to be done in very specific areas and only when it is “necessary” and “reasonable”,” stressed Sharom who is also an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Malaya.

Political hijack

It had become clear that the issue was hijacked and used as a smokescreen by Malay leaders from the previous administration for political mileage. However, rumblings of anxiety amongst the Malay population in the country were indicative in the months preceding.

A Merdeka Center poll in August showed that Malay voter sentiments slid to below 50 percent for the first time since the euphoric electoral victory in May likely due to heightened use of racially and religiously fuelled rhetoric by the opposition. However, this detail was likely overshadowed by the rousing approval rating numbers of the Prime Minister and his administration in the same poll.

As Malay opposition leaders vilified others for their support for ICERD, Minister in Charge of National Unity and Social Wellbeing, Waytha Moorthy was made the black sheep for his continued support for the convention’s ratification. His shambolic performance in Parliament as opposition lawmakers hounded him with accusations of treason and some calling him a racist helped cast doubt on the government’s strategy towards building a coherent narrative to support Malaysia’s ratification of the convention.

To add to that, a riot at a Hindu temple outside the capital city of Kuala Lumpur provided fuel to the growing inferno.

The opposition therefore had the perfect concoction at hand to mobilise support and cause a furore; pressuring the government to go on the backfoot. Playing to racial and religious sentiments in a country where race and religion has for the longest time been a permanent fixture in politics thus proved an effective strategy.

The ICERD debacle has been a critical test of the new government of Malaysia’s ability to tackle hot button issues like race relations in a multi-ethnic country.

On a more positive note, the 8 December rally came and went peacefully – with rally-goers even being praised for their behaviour and conduct during the protest. Despite incendiary speeches by some threatening to take up arms if their rights were challenged, no untoward incidents occurred – a nod to the inherent peace-loving and good-hearted nature of Malaysians.

Nevertheless, the agility in which Malaysia cycles through issues – impassioned by one but not for long as another distracts the nation’s collective attention – is enervating to say the least. This is cause for future concern for Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s cabinet as the ICERD issue won’t be the last of its kind to rattle the nerves of the country’s fledgling government.

Sadly, as the political narrative becomes more convoluted with each passing issue, it is ordinary Malaysians who have to suffer the brunt of it.