Photo Credit: Cambodia, P.I. Network/Flickr

Conditions in Cambodian garment factories are improving, according to a new UN survey, but rights violations are still rampant.

By Skylar Lindsay

A recent survey by UN initiative Better Factories Cambodia (BFC) shows that conditions in the country’s garment factories are improving. But the sheer number of rights violations that still occur make it clear that garment companies need to build new mechanisms for accountability and transparency.

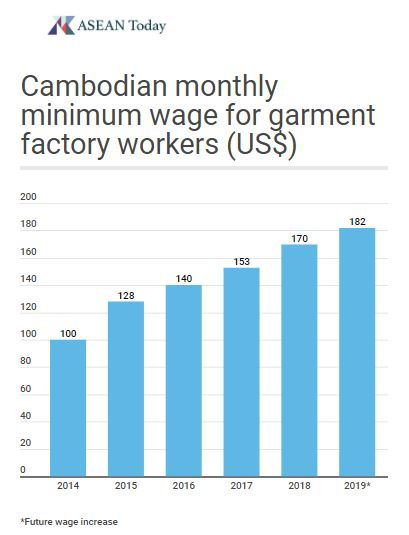

The monthly minimum wage for garment factory workers in Cambodia is now US$170, up from $100 in 2014. The Hun Sen government and the international “race to the bottom,” in search of ever-cheaper labour, have created an economy that forces Cambodians, especially women, to rely on these low-paying jobs that still expose them to rights violations.

Source: Better Work

As the garment industry plays an ever-larger role in Cambodia’s economy, it’s crucial that the Cambodian government, garment industry corporations and international allies support the Cambodian people in pushing for transparency, accountability and better conditions.

Compliance is improving in Cambodia’s garment industry

The BFC report found that compliance had improved for international laws around overtime wages, discriminations against employees, child labour, routine evacuation drills, and reprisals for union membership. The survey considered 21 critical issues and found that 44% of factories were fully compliant with international labour standards and national labour laws for these areas, up from 33% during their previous survey.

This represents a substantial improvement, but it still means that over half of Cambodia’s registered factories may be violating international law. Across the nearly 500 factories surveyed, BFC still found 234 violations between November 2017 and May 2018, though this is down by 329 violations during the last reporting period.

57 of the factories showed clear cases of discrimination, nine factories committed forced labour violations, and 155 factories violated workers’ rights to freedom of association – this may be why there were only nine strikes over labour disputes reported (down from 147 in 2013).

Just this week, workers from the Prestige Garment factory have been protesting the firing of a fellow worker who tried to form a union. Over 1000 workers from the Seduno Investment Cambo Fashion also rallied to demand severance pay that was deducted from their pay.

The compliance percentage likely increased because 114 of the factories in BFC’s survey pool shut down. Many of the closed factories were in violation of the laws and standards that BFC considers in its survey.

The BFC report suggests that this demonstrates how poor labour standards are bad for business, but it could also be that the noncompliant factories shut down, moved or changed their operations and avoid scrutiny.

The actual working conditions also appear to still threaten the health of workers. According to the Cambodian government’s own statistics, over 2000 workers fainted in 2018 in just 16 factories that were surveyed. In one shoe factory in October, nearly 100 workers fainted during a single shift. High temperatures in working spaces, chemicals used in the manufacturing process, or overwork are all factors that could cause workers to faint.

In terms of child labour, the survey found only 11 violations of international child labour laws among 600,000 workers, far fewer than the 74 violations found in 2014. But there’s a good chance that children have simply stopped working in the licensed factories, working at home or with subcontractors instead.

Also, the chief way that child labour violations are identified is by catching workers using false documents to prove they’re of age – 15 years or older. It’s possible that many more children are now simply passing these checks unnoticed. Improvements like these are hard to verify and the violations still indicate an opaque and weakly regulated industry.

Some of the improvements that supposedly represent progress aren’t much cause for celebration. According to new recommendations, pregnant women are now allowed to leave work 15 minutes early and are given a benefit of 400,000 Riel (about US$100) for having a single child. These concessions may signal improving conditions, but they also demonstrate severe gender-based discrimination.

The industry is crying out for new accountability mechanisms

These statistics may show that the Cambodian government is willing to own up to the inevitable struggles within the garment industry, but government involvement is a glaring shortcoming of the BFC report.

BFC is a partnership between the International Labour Organization and the Royal Government of Cambodia, as well as the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the governments of Australia, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the US, not to mention Levi Strauss and Gap.

Partnerships with the Cambodian government are important, but when they’re involved in reporting and monitoring rights violations, the resulting data is questionable. Transparency and accountability must come from independent bodies, free from conflict of interest.

Also, the BFC survey was only able to look at licensed garment export factories. In Cambodia, 85% of the population still works in the informal economy.

After the release of the BFC report, Dy The Hoya of Cambodia’s Center for Alliance of Labour and Human Rights told the Thomson Reuters Foundation, “I do not see any change in the informal sector.”

The outsized role of the informal economy and the conflict of interest inherent in the BFC survey show that corporations, foreign governments and UN bodies need to work with local Cambodian groups to built new tools to support accountability and transparency.

Cambodia’s garment industry is an economic timebomb

Sources: ASEAN Briefing, Just Style, Reuters

Recent data from the World Bank suggests that demand for Cambodia’s exported textiles is increasing at a rate of 16.1% per year, more than double that of the country’s economic growth rate.

This growth is partly due to the European Union’s decision to give Cambodia tariff-free access to their markets under the “Everything but Arms” (EBA) program beginning in 2012. Trade with the EU accounted for US$5.8 billion of Cambodia’s exports in 2017, and 46% of total garment exports were to the EU (24% were to the US).

Recent political events have thrown Cambodia’s special status into question and cast doubt on the future health of the Cambodian economy.

In October, the EU told Hun Sen’s government to address human rights violations and cease political suppression or face consequences, including the revocation of its EBA privileges. The EU has begun a six-month review of Cambodia’s trade status that will determine if they can continue trade within the EBA program.

Hun Sen’s violations of the UN Charter, the Lisbon treaty, and International Labour Organisation (ILO) standards on workers’ rights are also of concern to the EU.

As Sam Rainsy, an exiled Cambodian opposition leader and former Minister of Finance, recently wrote in The Diplomat, “if, to be able to survive, Cambodia’s clothing industry, a pillar of the national economy, must rely indefinitely on European trading advantages… then the European Union will be subsidising and financially rewarding, through the trading system, the corruption and poor governance of the regime.”

The EU cannot in good conscience continue to grant Hun Sen tariff-free privileges. The trade program is called “Everything But Arms,” but the garment industry has become a weapon to repress the prospects of the Cambodian people for a better future. The EU must support any efforts by Cambodian communities to diversify their economy and regain control from international garment companies.

Garment companies who profit from the broken industry must take responsibility

Despite rights violations in the garment industry and the country as a whole, Nike, Adidas, H&M, Gap Inc, and other international brands continue to rely on Cambodia for the manufacture of a significant portion of their products.

H&M recently hosted a summit on fair wages in Phnom Penh and stated that wages for factory workers producing their clothing were 24% higher than the minimum wage, for a total of US$210.80 per month. But when rights violations continue unchecked, H&M is kidding itself by calling this fair.

The Clean Clothes Campaign, a network that has been advocating for garment sector reform for 30 years, boycotted the event, citing H&M’s failure to follow through on its promise to make sure that 850,000 garment workers earn a living wage by 2018, by working with their supplier network.

ASEAN Today reached out to H&M for comment but received no response.

Better conditions in garment factories may increase the costs for companies, simply driving corporations out as they relocate to the next source of cheap labour, in the never-ending race to the bottom.

Hun Sen and his government appear content to allow the Cambodian economy to rely on this single industry, as they have for over two decades. This has created a ticking time bomb in the Cambodian economy. It is up to international governments and major players in the textile industry to push for meaningful change in Cambodia.

The beneficiaries of international capitalism – garment companies, the EU and other higher income countries – owe the Cambodian people a better option and a chance at self-determination.